The question is: how Fashion and Graphic Design influence each other and how is this relationship reflected on branding dynamics?

First of all Fashion and Graphic should be considered as both design practices. According to Munari’s theory Design is made by technology and communication, indeed the designer construes the range of symbols of a particular culture: that use of codified symbols is necessary to communicate a message to a huge audience and graphics represent the simplest and fastest way to deliver a clear massage.

Considering that a specific code transmits a specific information, Bruno Munari thinks Graphic Design as the main resource of an intentional communication. Based on this perspective, the information – given through an intentional communication – can be received by the beneficiary understanding all its meaning as much as the transmitting wants to reveal.

At this point this theory starts to became useful even in Fashion communication, because a message is made by two parts: the information itself and the visual stand (Munari 1968). In Fashion the information is represented by clothes and the visual platform is the graphic used for realizing the logo, or the visual approach of an advertising campaign, or also the architecture of a store. Recent studies underline that fashion brands work well when the shape of the label reflects the message (Teunissen 2013).

Thinking about the process behind designer’s work in this way, marketing strategies have become more complex in the last decades. Indeed, the most important tool for fashion marketing is branding, in other words the selling of item through its symbolic image: the brand itself. As Edwards states: “brands and logos triumph over design” (Edwards 1988) and sometimes also Fashion Houses could change themselves by rethinking their logo.

In the previous centuries, Fashion is thought as a mirror for the social identity of people, reflecting the hierarchy of the social classes. Clothes could be considered as signal of power and wealth. Lately, clothes have lost that function and become a tool to express people’s identity. Clothes wear identities (Edwards 1988): Fashion is not a representation of how people want to appear, but who they want to be.

In the contemporary society, dominated by celebrities and brands, this is a basic feature. Nowadays fashion is the fastest way of identity appropriation: by buying a Chanel dress the costumers are buying Chanelness; by buying a parfume sponsored by Charlize Theron the costumers are buying Theroness. Costumers are allowed to desire alternative shapes of subjectivity.

I will try to focus on a specific brand (in this case Dior) to make more clear what I am trying to explain, and also to understand how the visual identity of a brand could be built, so it could be possible to figure out how the relationship between Fashion and Graphic Design have been changing during the time through Branding.

In this context Dior represents a clear example because its founder specifically wanted to dress a particular female image.

Dior’s brand is related with an image of a very feminine woman and a soft femininity. Dior’s image is connected with ideas of elegance and grace, romanticism, opulence and sinuous shapes. On the other hand a woman wearing a Dior dress wants to become a princess; she does not want just to look like one, she wants to be part of the brand-experience. Obviously, it is easier to buy a Dior belt or a perfume, than to buy an expensive and luxurious dress!

It is a repetition of dynamics: we buy a pure symbol to become part of it. Thereby buying Dior, costumers buy a piece of pure femininity.

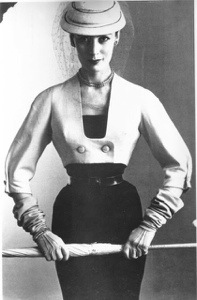

Christian Dior started his career as a couturier in 1947 when he launched his collection Corolle. The name of his first collection referred to the shape of the garments, which recall flowers and softness. The collection was inspired on one hand by nineteenth- century costumes, and on the other hand by clothes from the Thirties, recalling a period of happiness and well-being. Indeed, the Second World War had its end a couple of years before Dior started his activity. During the war, there were strict restrictions on the purchase of clothes and textiles because of a lack of raw materials, so everything was regulated. Therefore, womenswear was mainly made by poor fabrics and badly designed: women looked like soldiers or boxers, as Christian Dior himself said in those days (Gnoli 2012).

Referring to the elements destroyed by the war Dior built a new image of women, starting to dress not just bodies but also identities, a specific female identity: the same identity that is embodied by the French brand even now.

It is commonly known, the success of the maison has been astonishing. It has been possible also thanks to the work of the French fashion illustrator René Gruau, art director of the advertising campaign for Dior in 1947. His illustrations recall soft features, elegance and sophisticated women on the same line of Dior clothes.

This collaboration made it possible to maximize the impact of New Look and stabilize Dior image, which became the leading image of the postwar woman.

Recently, under the artistic direction of John Galliano (1996-2011) something changed, giving us an interesting case study. Under Galliano’s direction the fashion house produced very glamour and dreamy dresses, taking the image of Dior to the extreme. Clothes became more similar to theatre costume, and the fairy-tale atmosphere aroused by them was overemphasized: Dior collections were still romantic and full of diorness, but sometimes unwearable.

In the late Nineties the economic growth authorise people and costumers to require a high end fashion product, so even the dreamy and unwearable glamour sponsored by Dior was in any case suitable for the market demands. The most important point was to create a specific imaginary, in which luxury haute-couture was the keystone of a huge market made also by accessories, perfumes and basic garments saleable through the image built by the brand.

Nevertheless, after the 2011 massive financial crisis in Europe, the sparkling atmosphere sponsored by Dior became too extravagant and a more wearable womenswear was necessary. Therefore, after Galliano’s collections the maison re-started to produce clothes recalling the idea of a tactful flower-woman, accordingly to the image of Dior in the late Forties.

In conclusion I would underline that there is a practical and theoretical gap between the older image of the couturier and the modern fashion designer: Christian Dior as a couturier dressed historical needs; instead Galliano as a creative director dressed saleable images.

References:

Edwards, Tim, Moda. Concetti, Pratiche, Politiche, Giulio Einaudi Editore, Torino, 2012.

Munari, Bruno, Design e comunicazione visiva, Laterza, Bari, 1968

Pecorari, Marco, “Zones-in-Between: the ontology of Fashion Praxis”, in: (ed.) Jan Brand, José Teunissen. Couturegraphique, Breda Moti/Terralannoo, 2013 p. 58-95

Teunissen, José, “From Label to Total Look, the various routes to merkidentity”, in: (ed.) Jan Brand, José Teunissen. Couturegraphique, Breda Moti/Terralannoo, 2013 p. 16-47

Gnoli, Sofia, Moda. Dalla nascita della Haute Couture a oggi, Carocci, Roma, 2012